Attack of the Killer Bush Pig

It took me a minute, maybe two, to figure out what was going on. Sassandra, my target, had just dumped a lovely pile of poo and I was readying myself to claim it as soon as she descended the throne. Beside me Hamimu stared off into the twist of vines and said, “Bush pig,” pointing. I looked, but I didn’t really look, because I didn’t really care. I’ve seen lots of bush pigs. Mostly they are just flashes of hair and bulk that tunnel off through the machaka (a general word for all the vines and thorns and sticks and trees that make following baboons so darn difficult) and therefore not very exciting. But this bush pig wasn’t running, which was a bit odd. I couldn’t see it, but it was sort of huffing not far off and then the next thing I know, Hamimu is picking up rocks and throwing them at it. My first thought was, “That is bad for data, Hamimu! Stop throwing rocks!” But I was also fixated on Sassandra’s poo and the two competing stimuli caused me to freeze somewhat stupidly and stare off toward the noise in front of us. The next words out of Hamimu’s mouth were quick and terrifying. I registered them each in turn. The first was, “Babies.” The pig has babies, I thought. My mind turned this over for a moment or two, conjuring up useful data such as, “Never get between a mother bear and her cub.” The seeds of alarm had been planted. Hamimu’s next words were, “Grab the sample!” I looked at my fanny pack, full of gloves and other useful scientific paraphernalia for collecting samples, and then at Hamimu, somehow unsure. Not waiting for me to work things out, Hamimu tugged a latex glove out of his pocket and lunged for Sassandra’s poo, sweeping it up in his hand and forming a sort of poo baggie out of the glove. His final word was, “Run!” I looked around me. There was nowhere to go. To the front and left were bush pigs, to our backs a thick wall of machaka. Hamimu started to climb a tree. I watched him, a little addled, and then saw a piglet start running toward me and finally I realized what was happening. Baboons were hunting bush pig babies. And mama bush pig was none too thrilled about it. Shit, I thought. The only thing to climb near me was a sort of dead log that put me exactly one foot of the ground. I yelled at the piglet to run somewhere else. My heart was in my throat. Next to my log was a tree that was about three inches thick, straight as a pole, and utterly devoid of limbs save one thin dead one. “Climb higher!” urged Hamimu. I couldn’t. Not really. Then mama showed up. This encouraged me to try anyway. I broke off the dead branch and lodged one of my feet on the remaining nub, and then used my arms to pull myself up a bit higher before thrusting my second foot flush against the tree as high as I could so I was sort of hanging there in a sort of flat-butted sitting position. I looked at mama. She looked at me. I recalled that bush pigs can’t see very well (Just like T-rex in Jurassic Park! I thought, helpfully) and hoped if I hung completely still she wouldn’t see me. Her piglet snuffled around underneath her. I recalled the sheer size of the teeth in the bush pig skull we found last month and took a deep breath. Then a second piglet squealed by, pursued by males, a puncture wound in its side spilling intestines like silly string. Mama and the other piglet moved off and soon they were out of sight again, though we could hear the terrible screams of one of the piglets being devoured alive. Hamimu and I swung our heads wildly, trying to figure out how to get away. Baboons darted past us, nervously, stealthily, and I was surprised by the quietness of the whole venture. All we could hear were the pigs. We saw mama again and Hamimu said, “If mama moves farther away, we need to run for the ravine and then the path.” At least, that’s what I think he said. Mama huffed off a minute or two later, and we both scrambled down our trees and beat it hard through the machaka, me crawling on my knees and not noticing the thorns sticking into my arms and legs. When we reached the path, we both smiled and laughed with relief and I radioed Jessica to tell her that we almost got gored by a crazy bush pig BUT we got the poop!

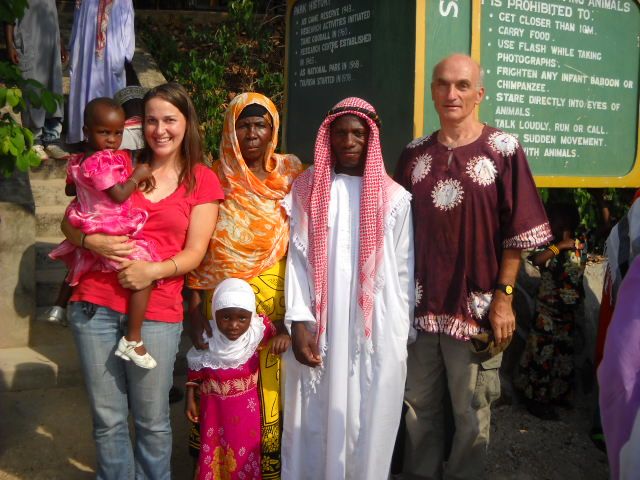

Harrison and her pig-filled pouch. Her daughter tried to get a taste but baboon mums are not great sharers.

The hair-raising part of the episode mostly ended there and then morphed into the baboons-fighting-over-the-dead-children-of-other-animals portion of the morning. This section involved a lot of in-fighting and males threatening one another and throwing out rapid broken grunts (RBGs) while females furtively skirted the kill site. My new target, Harrison, proved herself to be the ballsiest baboon next to one-eyed Salad (the female who broke into my house and continued to shovel bananas into her face as I beat her with a pillow). Her current boyfriend, Achalle, had to make the tough decision between booty (in the pirate sense) and booty (in the biblical sense), and when he ditched Harrison for pork, Ubungo, her abusive previous boyfriend swooped in and took over. But Harrison didn’t care. She had a mission. And that mission was to get her piece of that little piglet. So, she bided her time and watched the boys bark and gnash at one another and when Achalle took off after a challenger she swept in, grabbed the carcass, and booked it. Despite several challengers, male and female, Harrison, with the help of Ubungo, managed to maintain control over the piglet for an impressive amount of time. Ubungo was not keen on sharing with his lady-love and routinely slapped her across the face like they were auditioning for a domestic violence movie for the Lifetime channel. But Harrison mostly just took these slaps, ignoring some and screaming like a banshee at others, but she always kept her eye on the prize, shoveling bite after bite of tender young flesh into her cheek pouch until it was bulging like a goiter. She eventually lost the carcass to Achalle, whom we left devouring what was left to devour while the heavens rumbled overhead. All I can say is that I have developed a more healthy respect for bush pigs. And the need for upper body strength.